Nasa space probes document big impacts on Mars

Space probes have witnessed a big impact crater being formed on Mars – the largest in the Solar System ever caught in the act of excavation.

A van-sized object dug out a 150m-wide bowl on the Red Planet, hurling debris up to 35km (19 miles) away.

In more familiar terms, that’s a crater roughly one-and-a-half times the size of London’s Trafalgar Square.

And its blast zone would fit neatly in the area inside the UK capital’s orbital motorway, the M25.

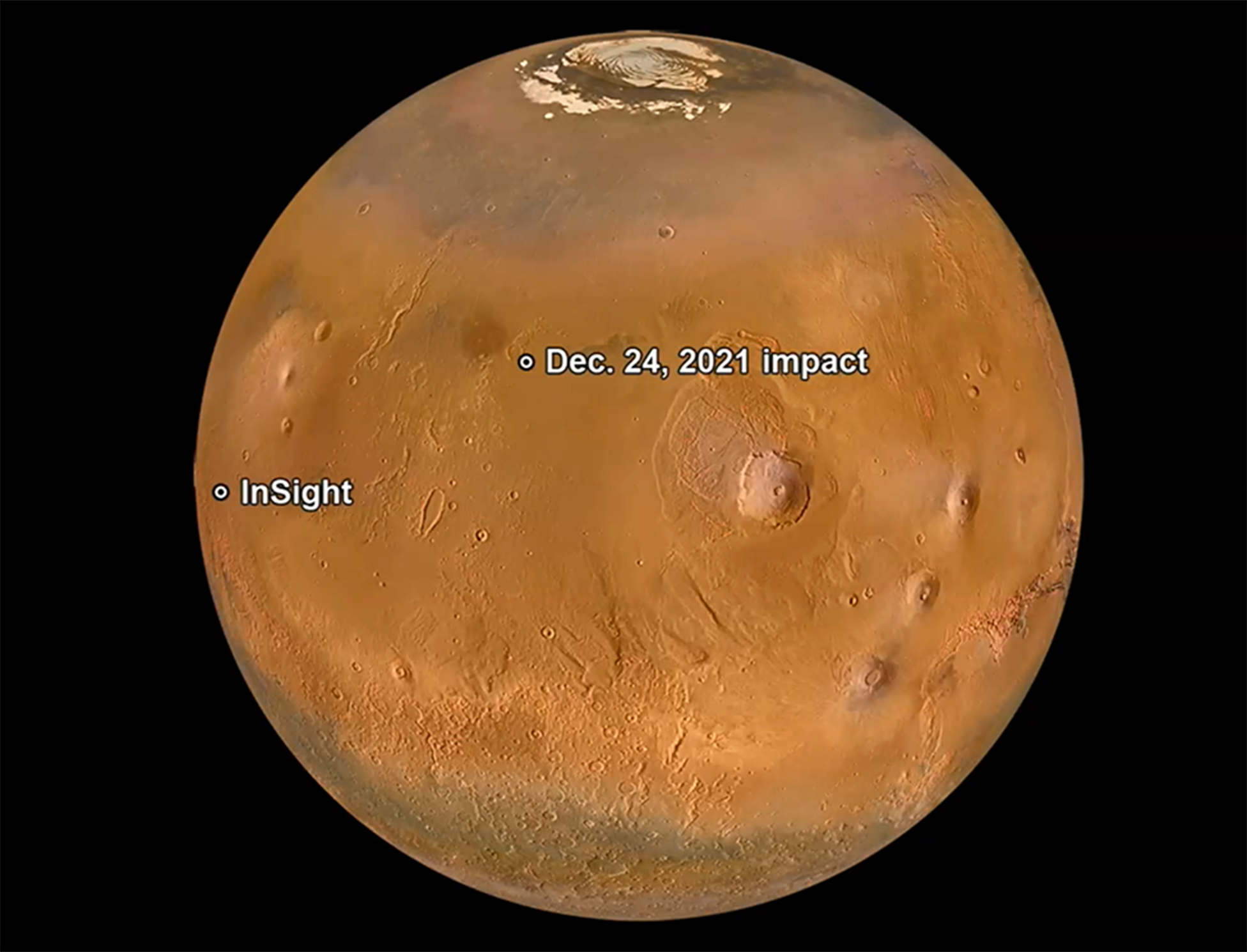

Scientists detected the event using the seismometer on the US space agency’s InSight lander. The probe picked up the ground vibrations.

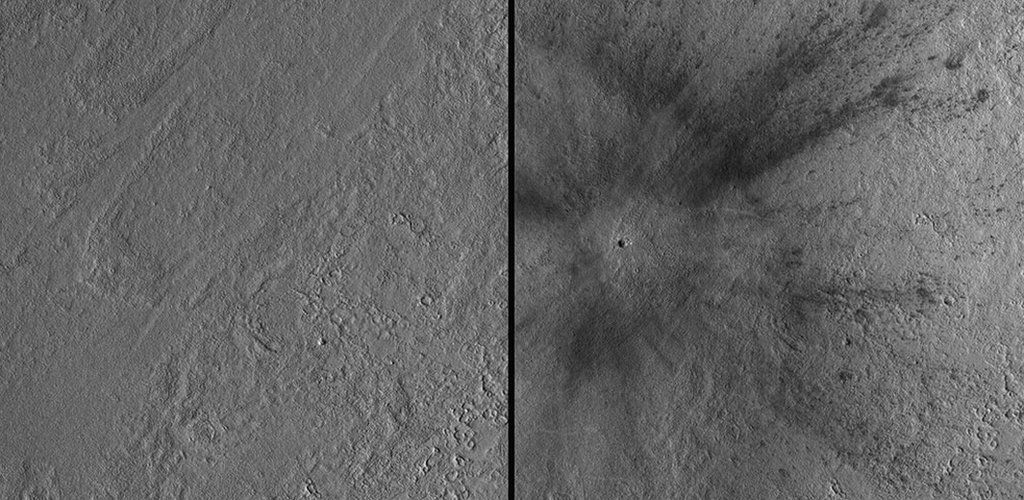

Confirmation came from follow-up imagery acquired by Nasa’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). This satellite routinely pictures the planet and could produce the before-and-after proof of a major surface disturbance, corresponding to the exact timing and in the expected direction and distance (3,500km) from InSight.

“This is the biggest new crater we’ve ever seen,” said Dr Ingrid Daubar from Brown University. “It’s about 500ft wide, or about two city blocks across, and even though meteorites are hitting the planet all the time, this crater is more than 10 times larger than the typical new craters we see forming on Mars.

“We thought a crater this size might form somewhere on the planet once every few decades, maybe once a generation, so it was very exciting to be able to witness this event.”

- Nasa’s ‘Marsquake’ mission in its last months

- Europe’s delayed Mars rover to get rescue package

- UK Mars rover will have to aim for the Moon

The post-impact observation shows huge chunks of buried water-ice have been excavated and thrown around the edges of the crater. Buried water-ice has never before been seen so close to Mars’ equator.

Such deposits would be an important resource for future human missions to the planet.

“That ice can be converted into water, oxygen or hydrogen. That could be really useful,” said Dr Lori Glaze, Nasa’s director of planetary science.

Using its French/UK-built seismometer instrument, Nasa’s Insight lander has detected more than 1,300 quakes on Mars since its arrival in November 2018. But the Magnitude 4 tremor resulting from this particular event, which occurred on 24 December, 2021, immediately piqued the interest of mission scientists because it contained a component of so-called “surface waves”.

The vast majority of quakes picked up by InSight have produced the traditional primary and secondary waves associated with rock movements deep within the planet.

These newly detected ripples were travelling in the uppermost portion of Mars, through its crust.

“This is the first-time seismic surface waves have been observed on a planet other than Earth. Not even the Apollo missions to the Moon managed it,” said Doyeon Kim from ETH Zurich’s Institute of Geophysics and a lead author on the scholarly reports appearing in Science Magazine this week.

The recognition of surface waves also enabled the researchers to identify a second meteorite strike. This one, on 18 September, 2021, occurred roughly 7,500km from InSight. It was a slightly smaller event and produced a cluster of craters, the largest of which was 130m in diameter.

Scientists think both impacts can provide fresh knowledge about Mars’ interior. Whereas the deeply sourced quakes tell them about the structure and composition of the planet’s mantle and core, the surface waves reveal new details about the overlying crust.

Researchers can tell that in between the InSight lander and the impact sites, the crust has a very uniform structure and high density. This contrasts with the previously reported three layers of low-density crust directly below InSight.

This realisation may have something to say, too, about the famous Mars dichotomy – the observation that the Northern Hemisphere is low and relatively flat, whereas the Southern Hemisphere of the planet is high and mountainous.

Researchers have wondered whether that’s because the crust in these regions is composed of different materials. But the new surface wave data and its suggestion of widespread uniformity in the crust would imply this theory is probably not the best explanation.

Dr Ben Fernando from Oxford University is an InSight mission scientist.

“InSight’s observations in the transition zone between the North and the South have been really valuable because clearly the crust evolved in very different ways in those regions of the planet,” he told BBC News.

“How and why they developed the way they did is still an open question, but I think these impact events have probably provided more understanding on this topic than anything else we’ve done so far on the mission.”

There are many craters on Mars, the consequence of billions of years of bombardment from rocks drifting through space. Some are true giants. The Hellas Basin is an impact structure over 2,000km in diameter.

But the 2021 impacts are significant because scientists have the instrument data recording the moment of their creation.

“Something like [the 24 December impactor] hits Earth a few times every decade, but burns up safely in the atmosphere or drops a few meteorites. We were amazingly lucky to catch this one while InSight was listening,” commented Prof Gareth Collins from Imperial College London.

The InSight mission is close to ending. Dust is settling on its solar panels, reducing their efficiency.

“In the next short amount of time, perhaps somewhere between four and eight weeks as best we can can predict, we expect the lander to not have enough power to operate any longer,” the mission’s principal investigator Dr Bruce Banerdt told reporters.